Collected data

COLLECTED DATA

SOUTHWIND

PROLOGUE

October 18, 2017, somewhere around Three Rivers, Michigan, USA

Max and I are sitting in a rented pickup truck, with the heating on, in the middle of the fields in the outskirts of Three Rivers. It is six in the morning and the sun has come up, but the sky is completely dark. A storm raged across the landscape and flooded the fields of brownish unharvested corn.

Our six-meter steamboat that we were preparing for our trip down the Mississippi was stored in the warehouse along the main road.

Vast fields as far as the eye can see; just the cornfields and woods. Deer are running across the road, pheasants are flapping their wings in the bushes. If it wasn't for the young oxy junkies at the gas stations, this would have been a true American dream. Still on the frontline, but idyllic.

A huge American flag was hung to dry on a porch next to the cornfield. The person who stretched it over the fence was vanishing in the shade of the trees lining the avenue.

Max and I pulled over in front of the flag. I opened the window and pointed my camera when Max suddenly whispered: "Look out, someone's watching!"

"What are you two doing here?" we heard from the shadow.

"Hello! We were just taking a photo."

"What were you taking a photo of?"

"Err, the flag ... and ... the cornfield."

"Um-hum, ok ... well ... yes, there are still a couple of patriots around here.

Let's go, out of the car."

The silhouette stepped out from the shade. Although it was literally freezing, he wore shorts, slides, a long beard, a hoodie with the hood over his head. He must have been around fifty. Just when I opened the door, a gun briefly flashed from underneath his armpit, and it was no pocket pistol, it was a Magnum, the kind Dirty Harry used to kill crooks. The one that makes big holes.

"What do you think about our president?"

Like I was shot with a gun; I went numb. My gaze was desperately pacing between Max and the bearded stranger.

"Well, I don't know him personally," Max said.

"Heh, smart answer," the man with gun said.

"And what do you think about your president?" Max asked.

"I think he's doing a good job for us," he proudly replied.

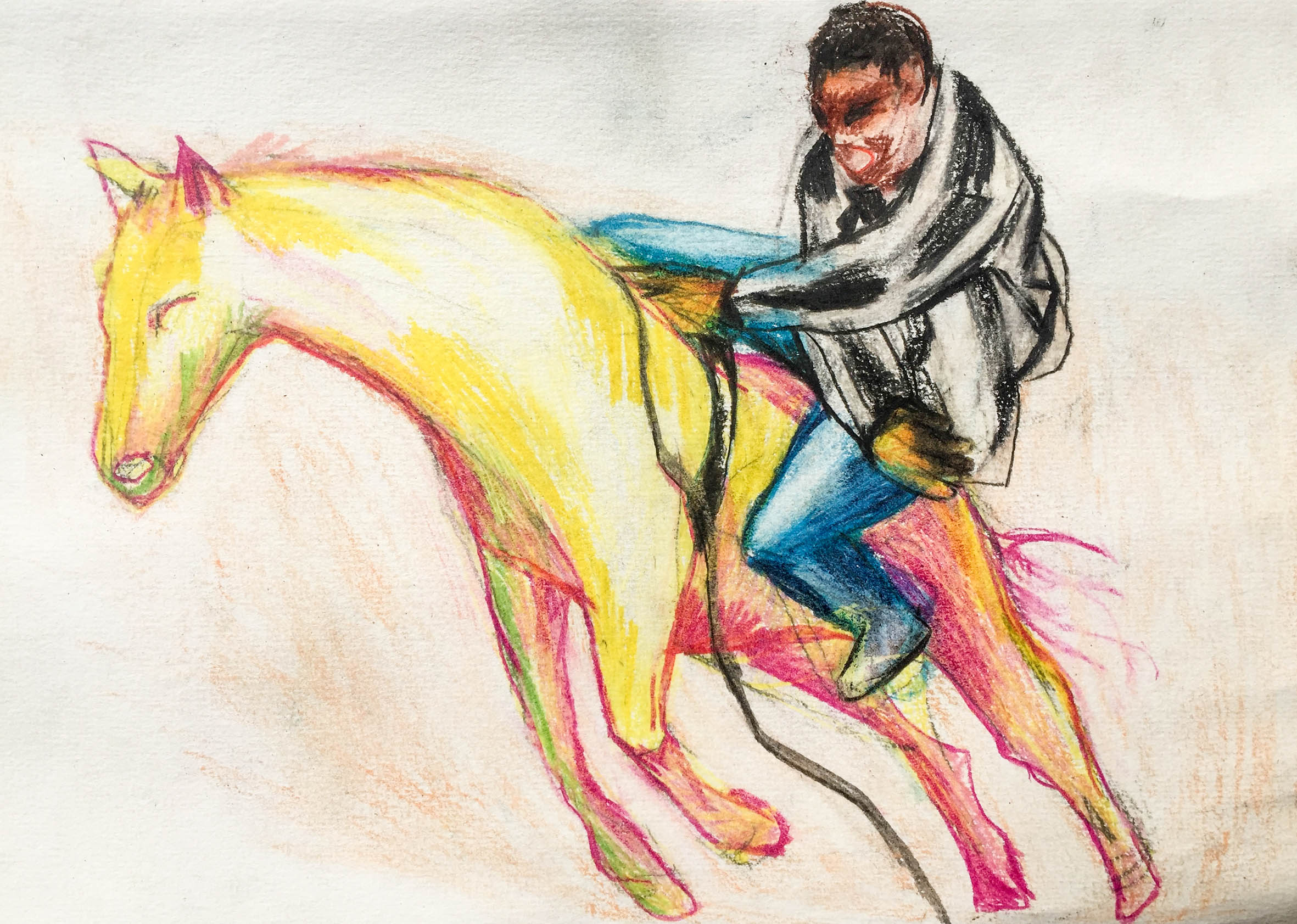

Born in socialist Yugoslavia in 1981, I had a romanticized image of the USA burnt into my conscience. I got my hands on the stories of Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer, and Dylan, Young, the Stones and the Zeppelin were blasting from the speakers. With Coca-Cola. With the first comic books featuring Zagor, Commander Mark, and later on Mister No, who all fought for higher causes and victoriously vanished in sunsets. With the Marlboro Man as life's driving force, on the edge of wilderness, answering to no one. With my father wearing a woolen sweater with an American flag, explaining to me this was the symbol of free speech, democracy and equality. With my first movies on videotapes: Robocop, Indiana Jones, Dirty Harry, Rocky, Rambo and Death Wish.

Of course, all these images would eventually change, fade away or take on new nuances, forms and meanings. But when Max and I started thinking about sailing the Mississippi, all these characters came back to life in a whirling cocktail of childhood emotions and euphoria. I could easily compare the feeling to an overly excitable dog overwhelmed with pure happiness, running around in circles with his tail tucked between his legs while his eyes glow with ecstatic joy and he drools so profusely he's spraying his saliva all around the place.

Mississippi!

We wanted to experience and investigate modern American society along the mythical river. We wanted to sail the length of the Mississippi River, from Minneapolis to New Orleans, 2,340 miles. To put it simply, we wanted to internalize the roles of Huckleberry Finn and Hunter S. Thompson.

In 2017, we bought a small home-built steamboat from an online ad. The owner had built it to sail the Mississippi; sadly, he was only able to try it out in the local lake, as he died soon after. The boat was six meters long. The steam engine was working, but we still had to build a roof so we could spend the month-and-a half long trip on it, as we planned. It stored at a warehouse in a small town of Three Rivers, Michigan, for two years, and we visited it every once in a while, as money and time permitted.

We intended to finance our Mississippi adventure by selling moonshine that we would distil in New Orleans, our final destination, from the corn obtained from the local farmers along the entire trip. The upper part of the Mississippi River – Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois, and Missouri – are a part of the so-called Corn Belt, a region that dominates corn production in the United States. Of course, the way corn is farmed defines the entire environmental and social picture of the river. For 2,000 liters of moonshine that we decided to make, we needed two tons of corn. The spirit is not very good, but it is authentic and legendary. Fifty or more percent of alcohol by volume – that's 100 proof or more – directly distilled from corn, no additives or barrel-ageing. The recipe was brought to the States by Scottish and Irish immigrants somewhere in the early 18th century. It only became illegal and highly sought-after during the prohibition, from 1920 to 1933, as it could be made cheaply and fast. It was distilled illicitly, in hiding places in the woods, sheltered by the night. Hence the name, moonshine.

Three Rivers is far from the Mississippi. On our visits to the States, we had driven twice along the entire Great River Road – the roads following the Mississippi River through ten states: Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana. But travelling by car, you only watch the river from the banks. You feel its presence, how wide and long it is, but you do not feel the currents, you do not know what is hiding underneath the muddy surface, what a storm can bring along, how deep it is, how fast those big logs and tree trunks are carried, how the huge cargo ships sail, and what life with the river is like. So, the entire time, we were building our steam boat with a phantasmal idea of the Mississippi, and hoped for the best.

I

Our previous experience, Hogshead 733, had been painful. We had entrusted the restoration work on our boat, Soutien de Famille ‒ Family Support, to a carpenter who turned out, to put it politely, not to be the person we needed.

This time we decided to do the arrangements and some necessary work for the smooth running of our project ourselves. Beyond the logistical challenge of organizing a project in the USA from Europe, the real issue was to correctly anticipate the technical difficulties that we were going to encounter.

With each trip I carried more tools, which I then left behind, meters in metric systems to be able to make conversions into the imperial American units.

Every day was presupposed, every task anticipated.

For the works on the steam machinery that we could not do ourselves I wanted to hire the Amish, whose community is widely represented in this corner of Michigan and whose "traditional" know-how is unquestionable.

But soon, after a quick on-site investigation, the only Amish we encountered had Bluetooth headsets to discuss business with potential customers.

Our first disillusionment with the image of an American community.

So, it was a very ordinary plumber and his son who travelled from Chicago to complete the connections and check the steam engine.

At Three Rivers we received some nice surprises, particularly at Pub 60 Grille a few hundred meters from our site which we visited every evening. We found the same heads leaning on the Formica counter. In this decrepit bar made up of two prefabricated buildings, many men and a few women were doing the same as we were, they were “ending” their day with a big sip of beer.

The regulars had known us for a while, two Europeans in overalls, coming every season to this corner of America in the middle of nowhere to work on a steamboat.

This project intrigued the pub's customers. Lots of questions about the why, the how. Mississippi attracts fantasies, many have a story to tell, an uncle who caught a man-sized catfish, a cousin who drowned, etc.

Over time certain faces, Kyle or Dwayne, asked what we were doing, we felt they wanted to help us. When we were looking for something in particular, we would ask the bar patrons. This is how we made a stop at a lot where boats, tow trucks and pick-up trucks shared this wasteland. XXX, the owner, sold us one after the other a caravan window, a piece of sheet metal, a ladder. Because we were always stripping the same old motorhome, a Chevrolet Southwind, we decided to name our boat as well as our project after him. The south wind always brings bad weather.

We went there several times before he really opened his workshop for us. It was Ali Baba’s cave for a petrolhead, a heap of tools as precise as they were unique, all organised around a car lift where XXX was building a dragster piece by piece around an airplane engine.

Everything is possible in America. We regret not having met this man earlier in order to devote a little more time to him, to understand his history his passion.

XXX knew his region perfectly, and his passion for mechanics had enabled him to find at a lower cost THE part which could not be found ... Thanks to his good advice we bought much of the equipment that we were going to need later and, most importantly, we met Mark Bidelman, based on Bidelman Road near Pleasant Lake. With his ex-wife and another employee, he made protective tarps for the local recreational boats. Without hesitating for a second, he offered to make us tarps and mattresses for our bunks for free, a considerable increase in comfort for our spartan boat.

II

THE JOURNEY BEGINS

UPPER MISSISSIPPI

La Crescent, Minnesota

The phone rang, it was 8 a.m. Tony had already arrived at the agreed spot with his trailer carrying our steamboat. The voice on the other side sounded tired and fed up. He had been driving all night from Three Rivers and he wanted to get back home. Front windows of our steamboat looked like a bloody battleground of mosquitoes and all kinds of flies. Tony must have been in a hurry and really stepped on it on the highway. He backed the trailer towards the river and our steamboat slowly slid into the water. Max and I watched with careful anticipation; the last time it was in water was six months ago in a lake near Three Rivers. Everything seemed OK, it wasn't leaking anywhere. We tied the boat to the floating dock and started arranging everything for our departure planned or the following morning.

We got firewood, mostly oak, from the locals. We filled the entire cockpit with it, and tied some more onto the roof. According to our calculations, that amount was to suffice for two days of sailing. We weren't worried about the wood. It was a month after a flood that had lasted for six months – the locals said it was the biggest flood since 93 – and we knew the banks would be full of dry driftwood. As for other equipment, we didn't really bring much: two canisters of potable water, food for a few days, a pan, a small gas burner, tools, sleeping bags, some clothes and technical gear. We had two electric outboard motors and solar cells on the roof to charge the batteries for backup, in case of problems with the steam engine. The motors weren't really powerful and we realized they would be no match for the current, but we were too afraid to use a motor with a petrol engine because everything was so close to the steam engine boiler and the fire that had to burn the entire time we were sailing.

Two days ago, we had still been in Europe. I flew from Vienna to Paris where I joined Max and our tiny filming crew of two members, and we flew together to Atlanta and from there to Minneapolis. I love long flights. When all passengers take their seats and switch on their small screens, I am overcome by a sense of complete peace and calm that I just sustain with alcohol and airplane food. Despite the anticipation and excitement, I once again drifted into a moment of blissful timelessness. In fact, that is how I pictured our adventure: a month and a half of sailing on this mini vessel that would be our private universe and our ticket to all the parallel worlds running along the river. We had built a backdrop for a story and I couldn't wait for us to enter it.

We still had Airbnb rooms rented for the night, and we decided to spend the last night in soft comfortable beds. On the steamboat, we each had a wooden bunk bed, one over each side of the boiler, that came together at the bow. I installed a small partition wall at the point where our beds met, so we at least would not snore directly into each other's face. At three o'clock at night, we were awakened by a strong storm that had not been forecast. The wind was howling around the corners of the house, and splashes of rain were slamming against the windows. Afraid that the storm damaged the steamboat, we ran to the river. We had covered the cabin with tarp sheets, but we had not tested it and had no idea how it would weather such a storm. Quiet and worried, we slouched to the steamboat while the rainstorm continued its raging dance above us. Luckily, the boat was still there, unharmed and completely dry inside. Overjoyed and soaking wet, we crawled into the cabin and brewed our first coffee on the boat. We folded back the boat cover. Through the fragrant steam rising from our cups, we watched the subsiding storm slowly giving way to the new dawn. Mornings near Minneapolis are already cold in September. A thin haze descended on the river and lazily shuffled across the surface. Mississippi' stream is still slow here. It was the first morning with the river. We heard the chirping of small birds, they could be something similar to European swallows, black with a white cap, gliding down to the river surface, hunting for small flies. They were followed by gulls flying higher up. A pouch of white pelicans was gurgling from across the river, sticking their long beaks into sand, foraging for breakfast. They were soon joined by fish, most likely predators, also hunting for their morning meal. There were no alligators here, we were still too high upstream and too close to a big city.

At about six in the morning, we started the fire in the boiler. It got warm in the cabin, and the thick smoke coming out of our chimney was dissolving in the morning fog.

Steam power may sound romantic, but this is a long and laborious process. First, the boiler has to be filled with water. It is manually pumped directly from the river, into a spiral laid out around the boiler. The pumping lasts until the first drop of water drips out of the safety valve. Then, the fire is started in the boiler. Oak wood is the best, as it yields a lot of heat that lasts long. The fire in the boiler heats the water in the tubes surrounding it and thus generates pressure. It takes about two hours for the pressure gauge to reach the maximum point, which is number 160. If the gauge pointer goes beyond this mark, the boiler could explode. There is a safety valve on top of the boiler, which should release the pressure from the boiler if this happens. But it can also be done manually. To release pressure from the boiler, you open a valve on a tube fitted with a whistle that sounds a loud whooo – whooo – whoooooooo. When the pressure gauge reads between 110 and 130, you open the accelerator valve connected to the pistons. The gear lever should be in neutral. You then kick the starter that in turn sets the pistons in motion. The pistons turn the sprocket to which a chain is fitted. The gear mechanism was taken from a Hot Rod, you only had to gently push the lever forward from the neutral position, and it already shifted into first gear. The paddle wheel at the back started to slowly turn. Southwind was on its way.

The camera operator and his assistant recorded our departure from the pier. There was only enough room on the steamboat for Max and me, and we agreed for the film duo to drive along the river, following and recording us.

We sailed out slowly, in first gear. Tk-tk-tk-tk-tk-tk-tk-tk-tk-tk – the sound of the steam engine reminded me of the old two-stroke engines.

Jack Kerouac never sailed on the Mississippi, but he crossed it many times during his cruises over the vast American expanses. "And here for the first time in my life I saw my beloved Mississippi River, dry in the summer haze, low water, with its big rank smell that smells like the raw body of America itself because it washes it up." he wrote about his first encounter with the Mississippi River in On the Road.

We were sailing; not fast, but we were sailing. Red paddles behind us were turning and splashing, loud whistles came from everywhere, the chain was squeaking, the pistons were pacing up and down, and steal was hissing out of the tubes. It was so loud we had to scream at each other. We screamed and laughed, a roaring laughter. We were sailing.

III

It was the day after Labour Day, vacationers who took advantage of the warmth of late summer had gathered for this long weekend on the still “recreational” shores of this corner on the south side of Minneapolis.

When we launched our boat most of them had already left this little resort town in their disproportionate RVs. The few people still present curiously attended this baptism which took place without a spectacle. Southwind touched the Mississippi water quietly, without surprises.

After being rapidly dragged from the launching ramp to the floating pontoon where we could moor, the boat began to play its role and attract people.

The first questions were about its mode of propulsion: is it a steamboat?

Then about its origin: did you make it?

Finally, about our own origin: where do you come from?

After answering yes, partly yes and Europe, we said that we wanted to get to New Orleans aboard this boat. It didn't take much to start a discussion on any topic.

The combination of two Europeans wishing to navigate the entire river on a steamboat was enough to arouse the deepest fantasies.

Quickly the two men suggested we pick up the remaining wood they had brought for their weekend fires. We had no idea how much wood the boiler was going to consume, but it was already a good starting point.

The film crew assisted us and filmed us. All the time I kept one eye on the boat, one eye on them. I hoped that we’d quickly find a way to work, I motivated them to be independent, to take over the project, their point of view was welcome.

Paper, kindling, stump, blowtorch, that’s it, the boiler was heating up. We only had a vague idea how long it was going to take; we’d only used the boat once, for an hour at most, on Pleasant Lake in Michigan, which meant we had no experience.

While waiting for the pressure gauge to rise, I checked the pipes like a racing driver, I visualised the course of the water from the river to the wheel. Every chicane, every acceleration, every valve. I needed an overview in the hope of mastering this archaic machine.

Two hours later at 160 PSI the safety valve was activated. We could no longer build up pressure and had to leave. Without artifice, without the public, without difficulties, without noise, we were there, heading south.

The wheel was turning slowly, the boat was manoeuvring quietly, and at times it was as if we had been doing this all our lives. How was that possible?

A few hours later we had a more precise idea of what our daily life was going to be like for the next 50 days. We were navigating at an insignificant pace, 2 or 3 knots, sometimes 4. The boiler was indeed greedy, very greedy, Kenneth had warned us. The machine was so loud that we couldn’t communicate in any other way than shouting, but the crew slowly found their place.

The solar panels I had installed on the roof were working and we had electricity on board. This level of comfort reassured us, because the next few weeks promised to be rather restricted, although it was not fatigue that we feared but the fact of not being able to talk to each other during the day. However, thanks to our computers we could at least write and continue our transcription of the project.

The arrival at the first lock seemed to take forever, we had wasted so much time stuck in the shallows in the middle of the river. The first lesson was to stay in the channel despite our shallow draft, which made us think that we could cut the path and take shortcuts. When the lock keeper handed us the rope to tie us up, the sun was already low, the day was over in the blink of an eye. We had no idea if we were going to achieve our goal of getting to McGregor.

The pontoon that I had identified for our first stopover ended up revealing itself behind a wide metal bridge, Mark was manoeuvring the boat but missed it by a few meters, trying to go upstream so that we would arrive with more ease, as with a sailboat.

Night fell quickly in this time of late summer, the mist was setting in, and soon we had no visibility on our way. Only our phones told us where we were approximately. It was impossible to see if a tree trunk blocked our path or if we were in the channel.

At this point we try to go up the river, but we have little pressure left because Kenneth had told us that perfect navigation is when you arrive safely, boiler empty and fireplace cold.

We miss.

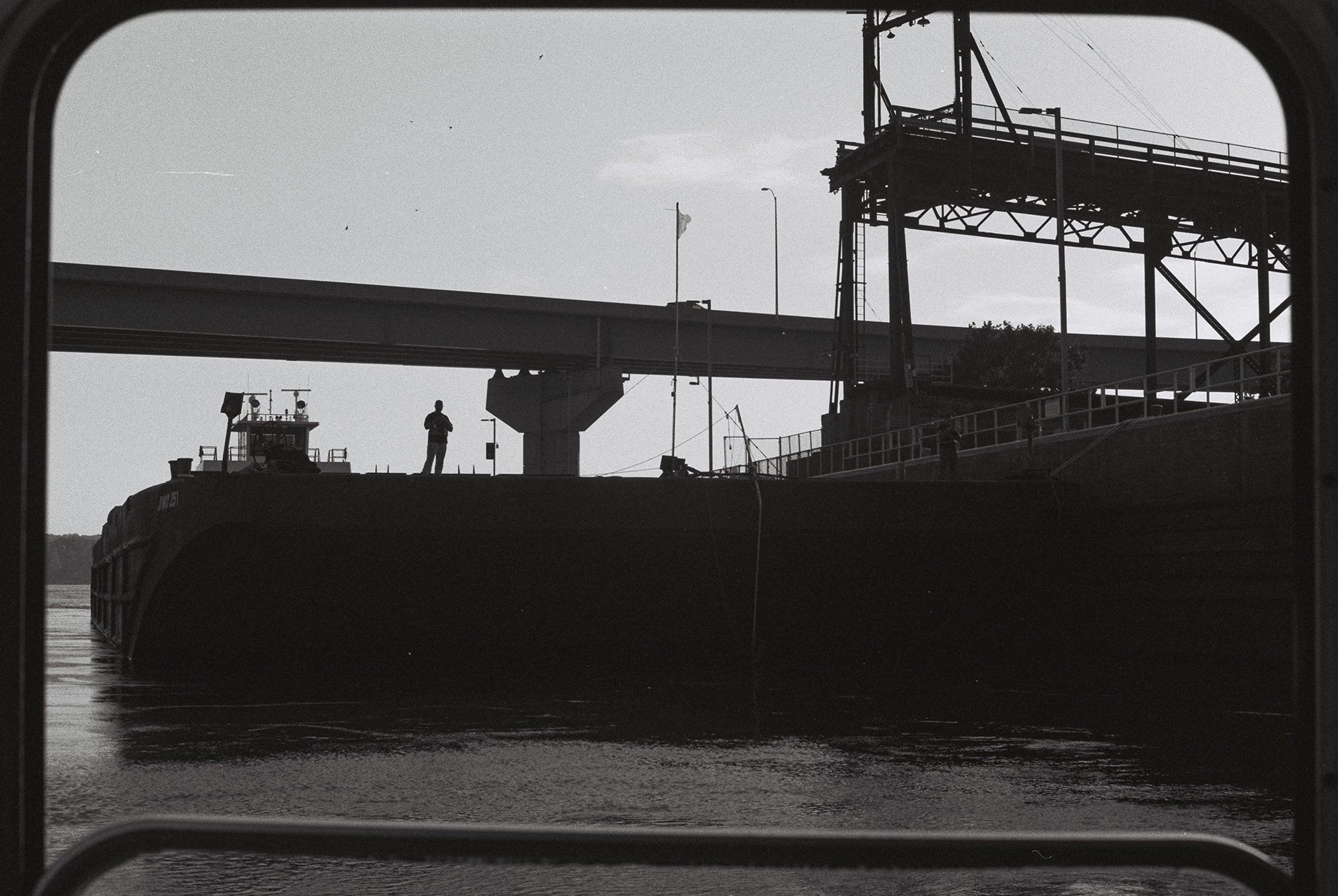

By blowing on the embers for 45 minutes, head in the hearth, I revive the fire that I had intentionally let die. Mark puts the electric motors to full force, but they are of no help, we gradually lose the battle against the current which takes us away from our goal and leads us to the centre of the river where it is stronger. Suddenly we are bathed in a blinding light, it is a huge projector capable of casting light for kilometres coming from the top of a pusher boat, with twenty barges in front of it. We think it’s there to help us, we wave to the boat which seems still far away, but we can’t get out of the current. We no longer have electricity for the back-up engines or pressure in the steam engine. We’re not able to manoeuvre a flat-bottomed boat in the middle of the Mississippi, and a city-sized boat is heading towards us. We drop anchor to secure our position, the pressure eventually allows us to move away from the waterway, and the pusher boat and its load avoid us. It quickly moves far away from us and only its overpowered headlight scans the shores and the surface on the lookout for any potential problems.

I still have my head in the boiler, blowing on the embers as if the danger were still imminent, when a much less intense light shines on us. It’s our film crew, who took the initiative to ask a fisherman on his way back to the port to assist us. From his motorised boat, a big guy with red hair throws us a rope and pulls us to the port of McGregor.

IV

Marquette and McGregor, Upper Mississippi

"What's the gauge say?"

"Kick that fucking starter already!"

"It doesn't work, the shit won't start, there's not enough pressure. Oh, fuck!"

Max's head disappeared into the darkness under the deck, and I could only see his forehead glow for a moment from time to time when he was blowing on the embers.

The boiler is a problem that requires constant attention. As if there was a third crew member aboard, that we had to deal with all the time. In the morning, you start and keep the fire for two hours until the water heats up enough to generate pressure for sailing; during sailing, you feed it all the time with wood to maintain temperature and pressure; and towards the evening and the end of sailing for the day, you start starving it so you reach the goal without fire, embers, and pressure.

"It’s all about time, boys," Kenneth kept repeating when we first tested Southwind on a lake near Three Rivers.

"Oh, shit!"

"The rudder won't help, we're spinning!"

"The current is too strong!"

"Anchor!"

I threw the anchor into the water. I was slowly releasing the line and braced for the tug. The line unwound to the end, but instead of a tug that would stop Southwind and keep it in place against Mississippi's current, I only felt how the anchor started to gently glide and sway across the muddy river bottom.

It was pitch dark. The lights of the Marquette harbour, where we were headed, drowned into the night with the relentless current. I turned the rudder a little too late. The filming crew was waiting for us at the pier, Max was standing on the bow with the line in his hands – but the current just swept us away. I steered the boat towards the current, but there was no pressure left, and the fire was out. We were rushing into darkness.

"It's rising! It's rising"

The flashlight was glancing the pressure gauge.

"Just a little more!"

"Try now! C'mon on, kick it for fuck's sake, come on!"

The starter turned and the pistons moved, slowly. I couldn't open the valve too much, otherwise I would use all the pressure that Max had just created. The paddle wheel was sobbing as it fought the current. It was still too strong. We were able to maintain course, but sailing against the current was impossible.

At that moment, a powerful floodlight brushed over us. It was cutting through the night like a beam from a lighthouse. I was naïvely delighted that someone from the river bank was lighting our way. In fact, it was a cargo ship, the first one we met on the Mississippi, sailing downstream, at least 50 metres long, going straight towards us. The hum of its engines coming from the dark gave us a frightening idea of its size.

"Yo, grab this rope and tie it up front.

I'll pull you outta this shit."

I was so fixated on the barge that I didn't even notice a smaller speed boat approaching form the other side. It was Dale, a local that our film crew asked to help us. His 110-horse-power engine roared and ten minutes later, we were safely moored in McGregor. Dale is a local teacher and he has spent his whole life on the river. He knows it like the back of his hand.

"When it gets wild, you better keep to the shore, and beware of the white caps on the waves," he shouted before cruising away. We stood on the pier of the McGregor marina, watched him leave, looked at each other, watched towards the river, and tested the solid ground beneath our feet. It all happened so fast we hadn't even fully realized we had just been inches away from shipwrecking.

McGregor is a small town where which access to the river bank is cut off by railroad. The train consists are huge, they can be one kilometer long or even more. The trains thunder by several times a day, always announced by a loud siren. They are all freight trains. Occasionally they stop and completely detach the river bank from the town. This can take ten minutes, an hour, sometimes even longer. People get stuck in their cars on one or the other side on a daily basis. They honk angrily, curse and yell.

When our adrenaline rush subsided, we realized we were starving. We had been sailing all day and there was no time for food. We double-checked all ropes, pressure, and whether there were any embers left in the boiler, and headed across the railroad into the small town. Actually, even calling it a small town is a bit of an exaggeration. It is a street with a gas station on the left, three bars and an antique shop. The lights were still on everywhere. The only person on the street was an old man in front of the antique shop. He had long white hair and a long white beard tied in a ponytail. He owned the antique shop and he introduced himself as Cowboy Jim.

"Come on in to Cowboy Jim's, welcome, welcome!"

"Cowboy Jim's got everything you need, just ask anyone, everyone knows Cowboy Jim!"

"Well, come on in already."

The antique shop was really full of all kinds of stuff. A cassette player with eagle feathers, mixtapes, woven tapestry, broken plates, photocopies of artwork, deer heads with just one antler ...

"Take a look around, everyone can find something."

"I used to be a junkie, but now, now I run this shop."

"Oh, that pot? Yea, that'll be great for the fire! Yea, yea, yea. Two bucks, two bucks."

"You're here by steamboat? Where from? Europe? I know it, I know it."

"You boys go to Spoonful and grab some wings and beers, and then come back to my place. Right there, see, take the steps and through the corridor. Room number 2."

I enjoyed the beer more than the wings. The memory of the experience on the river was still vivid. We were the only guests at the bar, and once they closed the door behind us, there were no more lights in the street.

Slightly reeling, we came to the building that Cowboy Jim had shown us. We walked up the squeaky stairs to the second floor and found ourselves in a dark corridor. A flickering light bulb revealed the brown-yellow walls with peeling paint and dried stains from the leaking roof.

There was a hand-torn piece of paper next to the switch with the handwriting: RING FOR COWBOY JIM.

We had no idea what was behind door number 2. But after the experience on the river, we were ready for anything.

"Hi-hi-hi, you guys came over, you're really here, good, oh yes, very good."

Cowboy Jim was stroking his beard and his belly and he was pacing in place from excitement.

"Step right in, come on in, right here, yea, through this door, yea, yea."

All of a sudden, a roof garden opened up in front of us, full of tomatoes and herbs. It was all there: thyme, sage, basil, lavender, rosemary, bay leaf. Compared to what we could get along the way, at gas stations that were the only store in smaller towns, where a slice of jalapeño in a frozen hamburger reheated in a microwave for breakfast was a vegetable bounty, this was heaven. A true culinary heaven.

"Here, grab a basket, just pick, pick! Oh, these small tomatoes are delicious!

Follow me, follow me!"

From the terrace, we went into another room. Huge columns of oyster mushrooms were growing in every corner. Cowboy Jim filled our laps with packs of dried mushrooms.

"C'mon, c'mon, hihihi!"

The next room was full of chest freezers. He opened one after the other, taking out chunks of smoked boar, deer, offering us steaks, chops, and veal. Our hands were full of delicious food of all kinds.

We saw ultraviolet neon light peaking from behind the next door.

"Just look at these beauties!" The black light gave away the contours of Indian hemp plants reaching towards the ceiling.

"I grow these for my own health. I've got stage four prostate cancer and no medicine can help me anymore."

"I want to stay alive for her," he added and showed us a portrait photo of a young woman on the wall.

"That's my girlfriend. She's 30 years younger than me, hihihihiiiii."

"Say a prayer for me, boys."

The next morning, he was with us at already at seven. He came with a big cowboy hat and a huge mug of coffee. His white beard was glistening in the morning sun as he shared his cooking recipes with us.

V

When Cowboy Jim got on board, he seemed a whole different person to the one we’d met the day before. He was, however, just as endearing.

Before continuing our journey further south, we decided not to tempt fate and repeat the problems of the previous day. It was obvious that the power of the steam engine would no longer be sufficient when the current and conditions were inevitably going to get tougher. Moreover, the electric motor was no longer of any help, as the system that we’d devised for recharging the batteries was past it. It was a bet we’d taken and lost. We thus went to the only store that was likely to sell a heat engine, which we were going to install to ensure our navigation. At the time we had no idea how necessary this modification was going to be.

We went to Spark Sport in Prairie-du-Chien, a store dedicated to hunting, fishing but also strong spirits, judging from the huge collection of bottles of bourbon, whiskey and other spirits that were curiously located in the same department as guns. There the manager welcomed us and offered the only engine under 100-horsepower he had in stock, as here boaters were not used to equipping their boats with anything less. We were gradually becoming aware of the power of the river.

The little 6hp Yamaha engine doesn’t have a long arm, and we’ll have to be inventive to adapt it to the hull of the boat without damaging the steam system. We are already late so we must not delay. After a visit to an ATM to collect the necessary sum, it's official: we don't have much money left for the coming days, but we have a new engine. The similarity with Freddy, the engine on our previous boat, is obvious, but we hope this one, which will never be baptised, will work better.

On the way back we made a stop at a gas station which was selling firewood. I’d spotted it months earlier while I was tirelessly following the river on Google Maps to mark our drop points as much as possible, to identify possible shelters and organise navigation according to locks, bridges, ports, marinas, roads, bars or gas stations.

For years, every evening before going to work in my little restaurant I’d spend an hour or two methodically following this route online. Every evening I tried to imagine our future navigation. I learned by heart each of the stages of our trip, the stops, what we had to do. Later during the realisation of the project, we were going to stop at these places, like this gas station that I already had the impression I knew by heart, and it was strange. But of course, I’d never been able to anticipate who we were going to meet.

Back in McGregor it is already too late to set off again, we prefer to work on the installation of the new engine and only resume navigation the next morning. The film crew must get back on the road to honour the Airbnb reservations we’d made. Taking into account this delay, we wouldn’t find them again until two days later if we managed to catch up. It was then that the multi-level organisation of the project was revealed. Having to deal with both remote shooting and navigation was exhausting. You had to keep one eye on the gauge of the steam engine, one eye on the river and its dangers, one eye on the map, and one eye on the phone’s screen to chat with the head cameraman and his assistant. It was also necessary to take advantage of what we were going through, to soak up everything for the purpose of the future transcription of the project. To be in several places at the same time. Great demands which would slowly consume me.

The monotonous landscape sometimes gave way to striking places, the river just a few meters wide from one side to the other widened without warning by several kilometres and gave us the feeling of the open sea with wind and waves. I found myself putting on my life jacket discreetly, and the prospect of swimming to the shore in the event of a shipwreck didn’t really make me happy.

At nightfall we ground the boat near an uprooted tree and use it to moor. We are on an island a few kilometres from a small town that we can vaguely make out. We jump on the muddy sand beach, collect the still glowing embers from the boiler and make a fire to give us some light and warm us up. The day was long, a simple meal was quickly devoured, and we went to bed without any delay.

In the early morning hours my forehead, hands and legs are covered with hundreds of insect stings and Mark’s ankle has tripled in size, swollen like a pincushion.

The itching is unbearable, the blood flows from scratching, nothing calms this burning sensation, and later a doctor, who I’ll meet by chance over a cup of coffee, will tell me these marks are caused by buffalo gnats and are not stings but bites. Today I’m still wearing the scars of their feasting that night.

Despite everything, we return to the beach to reorganise and cut dead branches in order to replenish our stock of wood. It’s damp and burns less well than the wood from the gas station, so we take turns at watching the fire to keep our pace and reach Davenport before dark. Before that we will have to pass two locks, and at the bend of one of them we’ll moor the boat at the floating pontoon of a public launching facility. There fishermen put their boats in the water to get as close as possible to the mouth of the lock, where eddies full of fish are formed. Some curious people approach us to look at the boat, one of them is a broken man, cap screwed on his head and a respirator in hand. It was his son who unloaded him there, before he went to get the pick-up, which will help them to lift their boat out of the water.

As soon as he gets on the pontoon the old man climbs over the hull and enters our boat, attracted by the old engine, in an instant he begins to question us about how it works, his sentences cut by lack of breath.

VI

Muscatine

We started our journey one month after a six-month flood. Some say this one was even bigger than the Great Flood of 1993. The river brings and takes away. When it takes, it's as if it came to collect a debt for the entire history. Some places were simply washed away. Many towns are empty and abandoned. A marina is marked on the satellite map, but when you reach the spot where it's supposed to be, the marina is gone. Sometime you find the entire marina a few miles downstream, shattered by the wild river and dumped in a swamp.

The first time we encountered this problem was in Muscatine, Iowa, a small town known for making pearl buttons from fresh shells out of the Mississippi. On the map, the marina seemed like the perfect spot to make a stop, protected from the south wind that had been causing us problems the whole day. As we approached, we saw that the floating dock was broken in half and covered with a sign: KEEP AWAY! PRIVATE PROPERTY!

The entrance to the marina was very narrow, but we gave it a try, hoping to find a better spot around the corner.

"Merde!" I heard from Max's side.

A broken part of the left rudder rose to the surface of the Mississippi.

Gravel and mud piled up at the river bend, so the entrance was too shallow. The rudder broke in half like a twig.

We couldn't sail on with a broken rudder. We stopped on the shattered floating dock and tried to repair it. I was standing on the pier of an abandoned marina with a huge axe, trying to shape a piece of wood into the missing part of the rudder, when a child appeared at the entrance to the marina. He could not have been older than seven, maybe nine years. He screamed at us that he was an officer of the law and that he would arrest us. His eyes were faint, only blackness staring at me. I could not tell what he was on, but it must have been strong. He came right aboard our steamboat and started grabbing everything he could get his hands on. He did not respond to anything we said. Everything around us was empty and abandoned, except for some people who occasionally crossed the parking lot close by, who looked like they were a part of the kid's gang.

When we grabbed the kid and tried to keep him away from the steamboat, he started screaming even louder.

"I am an officer of the law!"

"You do not tell an officer of the law where to go!"

"I am an officer of the law!"

"You crossed the sign! The sign!"

"I will arrest you!"

"Don’t touch me!"

"I am an officer of the law!"

I kept looking over my shoulder to see when his brothers or the rest of the gang would show up. Max was holding the kid, I fastened the last bolt of the rudder, started the engine, and we left Muscatine.

We sailed back into the Mississippi, and when I looked back towards the marina, I realized we had forgotten the mattress of Max's bunk bed on the pier. The kid grabbed the mattress, gave us a mean grin, and threw it into the water.

Mississippi – floods, flood management, transport, and corn

Mississippi has always been flooding. On our journey, we even saw small mounds, safe shelters supposedly built by the indigenous peoples, which stand witness to the river's shifts and to the way life with the river was being organized from the very beginning. The founders of New Orleans started building local floodwalls and levees already in the 17th century.

In nearly three centuries of flood management on the Mississippi Government policies and activities to deal with flooding have shifted from ‘let the locals do it’ to full federal responsibility for an essentially structural-only approach, to a federally led, locally shared mix of structural and non-structural elements, that are gradually being combined with other water resource activities in an integrated and comprehensive approach to basin water resources management. The sheer size of the Mississippi and the Constitutional authorities of the states lessen the ability of Government to develop a uniform approach.

The 75 years of comprehensive planning for flood management in the Lower Mississippi was initially focused on flood control and navigation and has essentially succeeded in meeting these goals. Over time, navigation and flood control interests have integrated environmental and recreational needs to begin to develop a more integrated approach.

(USA: Flood Management – Mississippi River, http://www.apfm.info/pdf/case_studies/usa_mississippi.pdf)

In addition to flooding, the population along the river, and the United States in general, are also concerned about the river's navigability. Transport along the river is much easier and cheaper than on land. Considering the amount of transported load, it is also better for the environment than road transport, despite the pollution caused by cargo ships.

As early as the 1830s, the federal government began improvements on the river in the interest of navigation. In 1930, after extensive studies by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Congress authorized the nine-foot channel navigation project on the Upper Mississippi River. This legislation provided for a navigation channel with a minimum 9-foot depth and a minimum width of 400 feet, to be achieved by construction of a system of locks and dams that create a series of slack water pools behind each dam, supplemented by dredging. Construction of this system mainly occurred in the decade 1930-1940.

In the approximately 670 miles of river between the first lock at the Falls of St. Anthony area of Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, and the last lock of the project (Lock #27) at St. Louis, Missouri, the Mississippi has a fall of about 420 feet. The purpose of the locks and dams is to create a series of steps which river tows and other boats either climb or descend as they travel upstream or downstream. Locks and dams on the Mississippi were not built for flood control or to eliminate all the low spots caused by shoaling on the river bed (buildup of sediment causing a hazard to navigation).

(US army Corps of Engineers, https://www.mvr.usace.army.mil/Media/News-Stories/Article/476805/whydowehavelocksand/)

Grain – mostly corn – accounts for the largest share of transport along the Mississippi with 60%, followed by oil and natural gas with 21% and coal with 19%.

The United States are the world's largest corn manufacturers and corn plays a major role in the country's economy.

Corn, or maize, was spread across North America a few thousand years ago. According to recent research, it was first domesticated and cultivated in the Balsas River Valley in south and central Mexico. Corn's ancestor plant, teosinte, is still grown in Mexico. Major new varieties were already bred by Native Americans by cross-pollination.

There are currently six types of corn grown in the USA: dent corn, sweet corn, popcorn, flint corn, flour corn, and heirloom corn. The largest share of the corn is used for livestock feed, followed by ethanol production, beverage production, and the food industry.

Most of the Upper Mississippi River is in the Corn Belt, a region of the American Midwest, which includes Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, and Missouri.

America, from a grain

of maize you grew

to crown

with spacious lands

the ocean foam.

A grain of maize was your geography.

(Excerpt from Ode to Maize by Pablo Neruda)

Corn farmers have two options to sell and distribute their crops. One is to sell the corn to elevators, i.e. huge granaries on river banks, from which corn is transported with cargo ships to New Orleans and further distributed worldwide. The other option are trains that distribute corn within the USA. Its price is constantly changing.

"It all depends on whether China is buying corn or not. And on the amount of corn produced in South America," said corn farmer Tim in the Booty Palace Bar near Hamburg.

The farmers we met usually don't really care what their corn will be used for or where it's going. Nr 2/sweet corn is the most commonly produced variety. Making ends meet, and possibly making s profit, is the top priority. Smaller growers are in a constant merciless struggle with the major corporate farms.

To mitigate soil erosion, a special farming technique was introduced in 1972, called no-till farming. In this approach, crops are grown without disturbing the soil with any kind of mechanical preparation, i.e. tillage. Use of this technique, however, allows for more weed growth, which in turn has resulted in increased use of herbicides.

"Off course we use GMOs, thank God they exist. In the seventies, I had to get a new dog every month. He would lick the corn and die," one of the corn farmers told us.

Genetically modified corn varieties resistant to glyphosate herbicides were first commercialized in 1996 by Monsanto, and are known as "Roundup Ready Corn". Bayer CropScience developed "Liberty Link Corn" that is resistant to glufosinate. As of 2011, herbicide-resistant GM corn was grown in 14 countries. By 2012, 26 varieties of herbicide-resistant GM maize were authorized for import into the European Union, but such imports remain controversial.

(Wikipedia)

All this, of course, affects the river, and the entire ecosystem around it. The Gulf of Mexico dead zone, just off-coast at the Mississippi River mouth, is one of the largest in the world. As the Mississippi empties into the Gulf of Mexico, it brings along excessive amounts of nutrients and minerals, especially nitrogen and phosphorus, dumped into the river along its course in the form of waste from the agroeconomic system, the meat industry, and sewage. This nutrient and mineral loading, also called eutrophication, results in algal bloom that robs the water of oxygen needed to sustain other marine life. Lack of oxygen, called hypoxia, is related to mass fish-kills in the Gulf of Mexico.

Watersheds within the Mississippi River Basin drain much of the United States, from Montana to Pennsylvania and extending southward along the Mississippi River. Most of the nitrogen input comes from major farming states in the Mississippi River Valley, including Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Nitrogen and phosphorous enter the river through upstream runoff of fertilizers, soil erosion, animal wastes, and sewage. In a natural system, these nutrients aren't significant factors in algae growth because they are depleted in the soil by plants. However, with anthropogenically increased nitrogen and phosphorus input, algae growth is no longer limited. Consequently, algal blooms develop, the food chain is altered, and dissolved oxygen in the area is depleted. The size of the dead zone fluctuates seasonally, as it is exacerbated by farming practices. It is also affected by weather events such as flooding and hurricanes.

(The Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone, https://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/topics/deadzone/index.html)

VII

After a stopover for a weekend, first in West Alton, Missouri, then in Alton, Illinois, we finally go through the last lock and enter the Lower Mississippi, the wildest and most unknown part of our journey.

Before that we’d completed a leg of navigation from Hamburg, Illinois, which was rather smooth, we even made a stop to meet a farmer who was going to provide us with corn from this state. He was the father of another farmer whom we’d had met earlier in Wisconsin, and who’d said that he preferred to settle over there rather than lower down the river where his father, was because for him that part of the river was too polluted. The father, however, was more interested in the corn production capacity of his land rather than environmental issues. A typical paradox, he presented himself as a man of the land, with a good farmer’s sense, who takes care of his farm so as not to harm nature and, incidentally, to guarantee consistent profitability. His solution was GMOs. A long debate on the pros and cons of this technology animated us for some time, without being able to reach a clear conclusion.

Still stirred by this discussion which shook our convictions, we see the West Alton marina on the shore of the Missouri. I’d called earlier in the week to see if we could stop there for two nights, and the captain told me there would be no problem if I paid in cash. He also said that on the evening of our arrival the port would organise a small party, it should have taken place earlier in the season but given the extraordinarily high water level it had to be postponed. We’ll be welcome if we pay in cash.

At sunset, with the boiler running out of steam, but with the help of our new heat engine, we entered the cove of the marina without any problems. We found a place in the middle of a dozen boats damaged by the rising waters, and we’d soon learn that these boats were not insured, that nobody knew if the owners would come to collect them, a sad sight.

We set foot on the ground and we head towards what seems to be the harbour master's office, but there’s no one there so we take a short tour of the house. A few minutes later our film crew join us, then a small group of people finally arrive and bustle around an empty pool to organise a small party. The captain comes to greet me, with recently dyed hair and beard, new pair of sneakers, you can tell he dressed his best for the evening. I escape the traditional questions, Where are you from? Where are you going?, and immediately mention that I want to sort out the rental of a place for the boat. After being relieved of 80 dollars, I ask where the toilets and shower are, because it was for this reason that we’d decided to stop here, as it was already several days since we’d had these comforts at our disposal.

Unfortunately, no, there’s neither. The flood damaged everything, all the plumbing is broken, hence the empty pool.

We’re thus a little annoyed, and very dirty, when we meet people coming to the party. We head towards a kiosk where a man offers us a beer which we accept with enthusiasm. We quickly forget our annoyances and get to know some of the occupants of the port, they tell us in turn what ties them to this special river. One of them tells us that there’s another marina, just on the opposite bank, which is entirely on a floating deck. It was not affected by the flood and we can find bathrooms there. Next morning we decide to check it out and then come back. I don’t know if it’s because of this plan or the beers but we spend a particularly pleasant evening listening and sharing anecdotes of freshwater sailors.

As agreed, we leave in the early morning for Alton, we’ve barely started to cross the river when we realise that it would be impossible to come back. The current is colossal, and despite the short distance to cover we’re already screwed. Too bad for our pre-paid place ... Our grief quickly subsided when we moored at Alton's main dock. Everything here is welcoming, there is a lawn, a small shop, toilets, showers, a washing machine and ... a jacuzzi. I’ll spend the next 24 hours in it, even if the temperature is well above 50 degrees, almost unbearable. Mark will spend his time at his desk: right next to my jacuzzi he sets up a plastic table and a chair, a parasol, an electrical outlet and Wi-Fi access. Absolute luxury. We savour these few hours because they allow us to forget the moments when we preferred to move away from the cities to isolate ourselves on small islands where we felt safe. In the previous weeks we were afraid of the social context at each of our stops, all these towns, these villages devastated by the flood and years of recessions had created a marginalised population, the left behind, drug addicts, homeless, and unemployed for whom the path of delinquency was difficult to avoid. A bitter observation that I made with my ass in hot water.

We even decide to stay one more day to fix some technical problems on our paddle wheel, which has been in heavy use in recent days. We’re also preparing to pass through St. Louis and see the arch, commonly considered the halfway mark of the river and therefore of our trip. It’s also the boundary between the Upper and Lower Mississippi, between the recreational part of the north and the more industrial part of the south, between the part regulated by the 27 locks and the part in the wild course, the boundary between the northern and southern states. It's a whole different river that we're about to navigate, and we want to be ready.

It was only after getting out of the last lock which had been blocked for several hours due to an electrical problem that we entered St. Louis under a blazing sun. We didn’t really have time to enjoy the passage in front of the tallest man-made monument in the country, because the swell tossed us violently and threatened our frail boat. The traffic is intense, as is this surreal "march" in the middle of the river that we descend in one go. The conditions are really dangerous, and we’re in a hurry to leave this place behind. A few hours later, completely exhausted, we reach Hoppie Marina, the penultimate marina before New Orleans, located more than 1,300 kilometres away.

As a kind of port, we only find a half-sunk platform barge, the rest has been washed away. Taking advantage of a powerful counter-current we manage, to our surprise, to moor with ease. Stunned by our tumultuous navigation, we approach a decrepit garage where two men are tinkering with the engine of an old pickup. Like something straight out of a movie.

One of them introduces himself as the owner's son-in-law. He tells us it's impossible to stop here, that the marina is full. Yet we’re the only ones, and we haven’t seen a single pleasure boat sailing for ten days. Faced with our perseverance, he ends up making a phone call to his father-in-law who’ll give the green light for one night. We won't even have to pay, even though we insist.

The atmosphere is finally warming up, we’re making small talk, he introduces us to his dog and even lends us some tools.

Night is falling faster and faster in the south. Exhausted we collapse on our wet bunks with our feet against the still hot boiler.

When we were preparing our project two years before, St. Louis was the first city where we visited our first rock concert with a psychedelic touch, the first city where strangers offered us a drink, our first glass of moonshine. When tasting this alcohol, Mark and I looked at each other from the corner of our eyes and said to each other "damn, how disgusting!", and now we were going to spend a long month drinking and learning as much as possible about this timeless, tasteless whiskey! Awesome.

Yet we had decided to produce this alcohol precisely because it was modest, it was the opposite of our previous project Hogshead 733, where Scottish single malt had aged in barrels made out of the wood from our 1941 sailboat. The result had been an extremely noble whiskey, and we wanted to do the opposite, a conceptual complement for our drift into the whiskey world.

Moonshine is also the Prohibition era alcohol produced from corn that was once mainly used to feed the young colonial nation. Today it is mainly used to produce ethanol, a synthetic substitute for petroleum.

When Prohibition hit the United States, many farmers were already producing ethanol from corn, not to run the country's internal combustion engines, but rather to quench the thirst of the people by distilling this abundant crop in the moonlight and thus produce moonshine.

The creation of this totally illegal drink led to the emergence of a parallel economy managed by the iron fist of the Mafia. Al Capone and his peers built empires and fortunes on the trafficking of this contraband alcohol. Crime got organised and the whole country followed the rhythm of rivalries between gangs and police raids.

To sell their merchandise, the mobsters created a network of underground clubs and supplied them with moonshine. To entertain and keep their customers, musicians were invited to play whatever they wanted. It was this forbidden context, soaked in booze, that accelerated the development of the blues in the south and jazz in the north. Later it would be rock’n’roll’s turn to take the central role. Three musical currents inseparable from American history, from which a good number of sub-currents still draw on directly today.

VIII

Lower Mississippi

The current in the Lower Mississippi was growing stronger. There are no more dams and the river can run freely. All the little tourist boats suddenly disappeared. Just the towboats with their clouds of dense smoke and strings of barges remained. There was more and more wilderness dotted with small industrial towns.

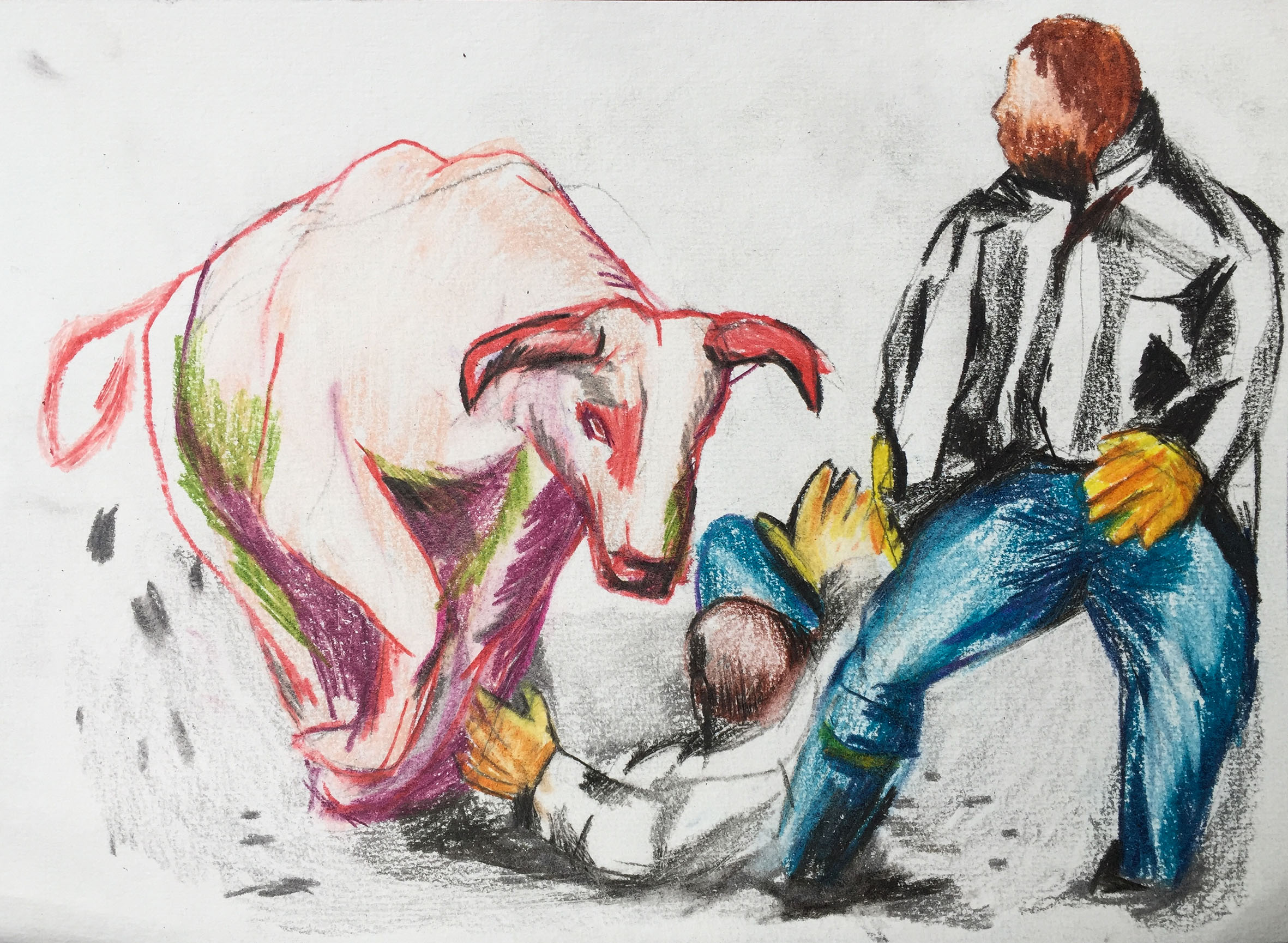

Just downstream of Cairo, we took a left turn onto the Ohio River. We removed the paddles from the paddle wheel and took on the 50-mile stretch of upstream sailing with our 6-horse-power Yamaha outboard. Our destination was Rocky Point in West Kentucky where our moonshine still manufacturer lived.

A green and a red floating sign indicate the part of the river where the current is the strongest. This is also where the river is the deepest and therefore safe to navigate. We sailed in shallow waters to avoid the current. We zigzagged up the Ohio River from one shallows to the next, hiding behind the corners of bays and crossing the current.

It was a sunny day, but a strong wind picked up from the south, causing ever higher waves. South wind is usually bad news; I am used to this fact from sailing on the Adriatic Sea, and it was no different here. For some time, we were able to turn the situation to our advantage. We opened up the tarp and used it as a sail. I'm not sure how much this really helped our motor, but at least seeing the tarp tight and full of wind gave us some hope. We were running our outboard at full throttle, but we were still moving at a snail's pace.

It was Max's time to take the helm, so I crawled to the bow, put on my mp3 earphones plus the earmuffs to block out the noise, and tried to relax a bit. I was slowly drifting away to sleep when I heard a scream. For a moment, I caught a glimpse of a huge fish, an Asian carp surely weighing 3 to 5 kilos, that jumped from the water and hit Max in the shoulder. The fish nearly knocked Max down. It bounced off of him, fell on the edge of our steamboat and back in to the water. The stench of fish lingered around Max long after that.

"If you see carps jumpin' out of the water, ya better watch out," Bayoo Bob advised us in a marina near St. Louis. "It means you're about to hit a concrete wing dam that's under water. Those carps like to hide behind them". (Concrete wing dams, or wing dikes, are man-made barriers extending partway into the river to reduce sediment accumulation, but can often be underwater and difficult to see.)

RASP and RRRRRRRRRR, and HRSK again. Our motor jumped up and barely hung on to its bracket. The whole steamboat shuddered. The lower part of the left rudder broke off and we saw it floating with the current. As it turned out, that Asian carp really was a harbinger of hazard. Bayoo Bob was right, we hit an underwater concrete wing dam. We lifted the motor from the water and found that of the three propeller blades, only two were left and one of them was bent. We tried restarting it. It worked, but its sound and the way it was shaking were not good signs. The steamboat and the motor literally shivered. We managed to pick up the part of the rudder that had broken off. Luckily, it broke at the same spot as in Muscatine. We sailed further 20 miles upstream with one half of our motor, until we reached the first public port where we could safely dock our boat.

Of course, we weren't able to buy a spare propeller for a 6-HP motor anywhere in Kentucky. Around here, even the backup motors have at least a hundred horse powers. The propeller arrived three days later from Amazon.

IX

Soldier of Fortune

"Pride is a sin," said our host and pushed the tip of his tongue through the gaping hole where his front teeth used to be.

"I'm not getting new ones," he said. "I cast away my pride."

"I don't cut my hair any more, either."

He wore his long blonde hair in a braid that rested on his back. His hands were full of tattoos, with a chainsaw taking most of his right forearm. He said he felled trees.

Max and I happened upon him a day earlier in the town of Paducah where we stopped after the ordeal with the broken propeller. We were standing at the bar when he suddenly turned to us and said his girlfriend wanted to buy us a whiskey. After a short conversation, he also paid for our dinner and all of our drinks, and invited us over to his place for dinner the next evening.

A flashing GPS point marked the spot in the middle of nowhere. I got the address in a Facebook message by his girlfriend, along with a note: "Bear is expecting you at seven," and "Bear has two wives, I hope this doesn't bother you."

We took our film crew's car and drove up to his house. The house was secluded. There were two large pickup trucks on the parking lot and woods behind it. Children were playing on the porch and two young long-haired women stood at the door, one of them blonde, the other one brunette, in denim hot pants. I recognized the brunette from the bar from the day earlier. She waved to us and invited us in.

"Bear will see you in his office."

From the porch, we went through a large living room, a kitchen, and down the hall to the door to Bear's office. Behind the door, Bear sat at a large desk that split the room in half. On his right was a large black safe; on his left, there were a grenade launcher leaned against the wall and a sniper rifle; on the desk, there were two Glocks and a computer, and a large screen on the wall displayed live reports from the cryptocurrency market. The first thing he asked us when we entered was whether we would like to try out the weapons. There was a shooting range in the woods behind the house. Max and I stayed with him in the office, while faces of guys from the film crew broke out into a big grin. Soon the rhythm of the Black Sabbath was punctuated with gunshots.

He sat us down. On two chairs on the other side of the desk, opposite him. Like we were being interrogated. I don't know how and why he picked us to share his entire life story with, but his tales were like an insane movie script. The information he put out at that desk was borderline fiction, but there was no room for lies in Bear's office.

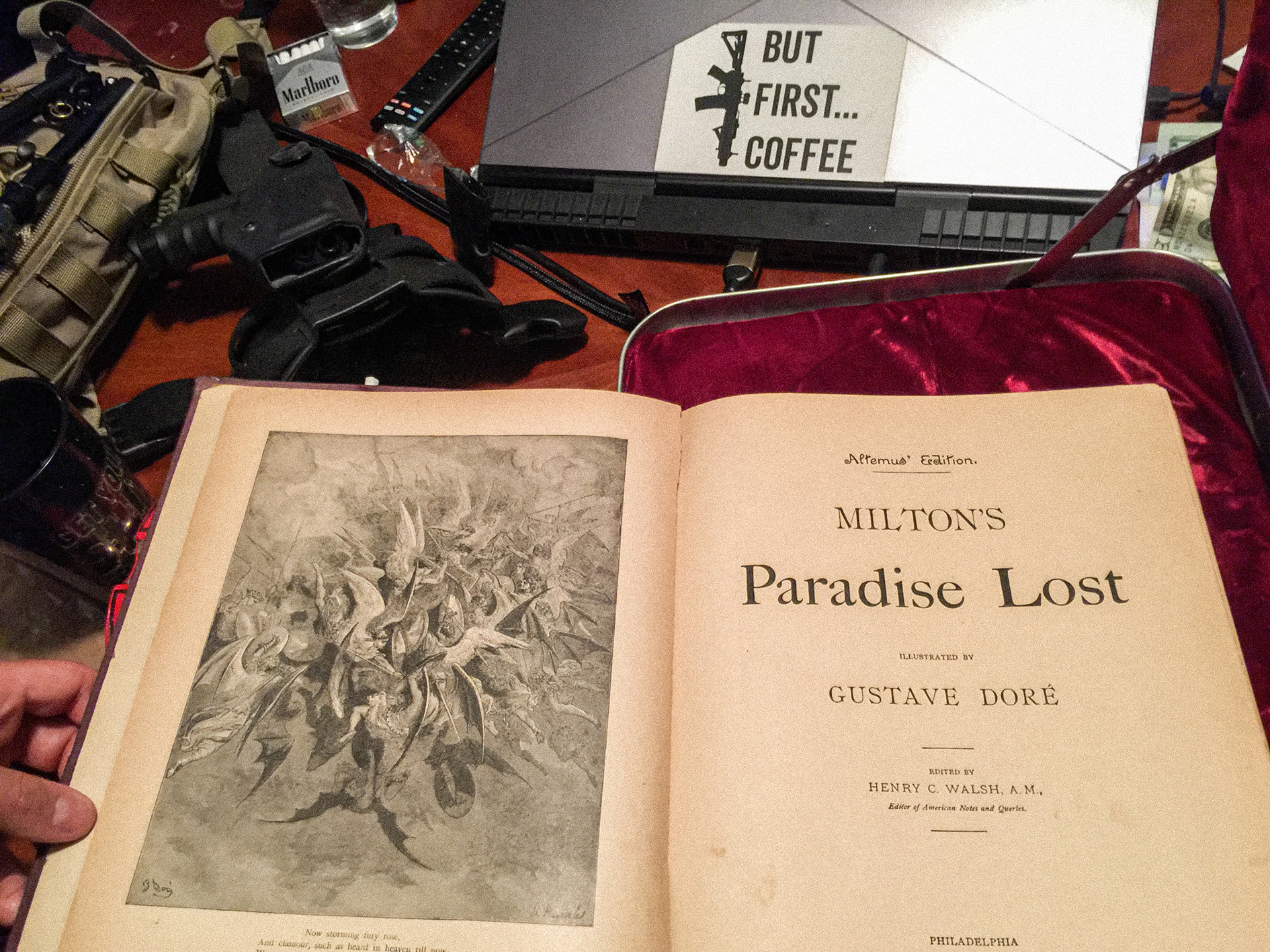

He was a mercenary. He fought in Iraq as a part of the Blackwater private military company, and later in Ukraine. Iraq was good money; he went to Ukraine because of his friends. He opened the black safe and threw a diplomatic passport on the desk. He has 23 children across the entire United States. Most of them happened while he was cruising North America as a member of the Hells Angels. He rode a large black Harley with waving flames at the front; he showed us a photo on his cell phone. Four of his children live with him, all of them boys. He looked very proud when he talked about his kids, as the youngest of them, still in diapers, crawled around. We drank whiskey and smoked Marlboro Reds. First an 800-dollar bottle, followed by a 1,200-dollar one. Bear again opened the black safe and took out a rare edition of Milton's Paradise Lost with illustrations by Gustave Doré. Latin quotes kept coming out of his mouth, one after the other. He took off his shirt and showed us a tattoo of skeleton hands holding his shoulders. "It's to keep me down to earth," he said. There were scars on both of his arms. "Both of them were torn off, they sewed them back on."

Despite our differing views on the issues of race, machismo, use of weapons ..., there was something about this enfant terrible of the American dream, walking hand in hand with death, that I found attractive.

"Who are you? Why did you say Ursus? How did you know this was my secret name in Ukraine? Who sent you?" he showered me with questions as he grabbed my shirt and pulled me across the desk with one arm. "I didn't, err, say any of that," I somehow mumbled and watched whether his other hand would reach for the Glock. It didn't, he let go of me. "Sorry, sometimes I get carried away. The shit I've seen there has left its wounds."

He filled our glasses for another toast.

He opened the black safe again and now it was time for presents. Bear presented us all with a pack of Cambodian banknotes, a military meal ready to eat, and an old revolver for Max and me – from a general to captains.

The right to keep and bear arms is protected by the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Second Amendment was based partially on the right to keep and bear arms in English common law and was influenced by the English Bill of Rights of 1689. Sir William Blackstone described this right as an auxiliary right, supporting the natural rights of self-defense and resistance to oppression, and the civic duty to act in concert in defense of the state. Fugitives, those convicted of a felony with a sentence exceeding 1 year, past or present, and those who were involuntarily admitted to a mental facility are prohibited from purchasing a firearm; unless rights restored.

(Wikipedia, Second Amendment to the United States Constitution)

X

Lady in Red

It was already dark when we returned to the driveway in front of the Airbnb where we stayed with our film crew while we waited for the spare propeller delivery.

"Would you like a glass of ice tea, young man?" a voice from the dark spoke to me. It was our landlady. Everyone else had gone into the house. The lady was a retired librarian in her seventies. Widowed, she lived alone on the farm with two white horses. She sat me down on a porch swing and brought me tea. We sat together on the swing, two strangers in a night so dark we could only hear our voices. Sometimes you need a stranger to talk about things you wouldn't share even with the people closest to you.

Her only son is dead. Murdered in a robbery. Killed by muggers he had never met before. "The good guys always win in the end," she kept repeating about her son. "I'm against American policy on guns," she said. "Many of my neighbours disagree with me. When my son was killed, I lay down in my bed thinking about how I could hurt the strangers that murdered him, or whom to hire to do that." She paused briefly. "I wanted them to suffer. And then ..., at the court, I looked in their empty eyes. I'll tell you, I believe there is something good in all of us. A few days after my son's death, my father gave me a hug. He was old, but he was a great man. It wasn't normal for him to show emotions. Through my tears, I heard him say: 'We must do everything we can to forgive these people.'"

We spoke of many things that night on the porch swing. We slowly rocked the swing with our feet, sometimes her, sometimes me. We talked about love, fear, resistance, faith, race and forgiveness. Although the KKK gathering point just around the corner from her house was only a fading memory, racial issues were far from being resolved or forgotten.

She wanted to see our steamboat before Max and I set off. As she asked to see the boat, her eyes were glowing like the eyes of a child. Max and I left very early. She was still asleep and we did not want to wake her up. When we sailed from the Ohio River back onto the

Mississippi, I turned towards Cairo and saw her on the beach. She was sitting on the scenic overlook where the Ohio empties into the Mississippi, and waved to us with her big red hat.

XI

CHOICES

Memphis, September 30, 2019

8:17 p.m.

After three weeks of sailing down the Mississippi with our six-meter steamer, we reached Memphis. We needed a few days' respite. A small transit pier, with a reception shack and cold beer, a few piers with permanent moorings, a toilet and the local crew that keeps moving their chairs around the shack to stay in the shade.

“You guys! What are you up to tonight?”

The voice belonged to a young man who worked in the marina. He was usually very quiet, hardly ever spoke. In the four days we’d been there he never even nodded, never mind said hello.

“Anna Alabama and I are going fishing. Want to come along?”

He’d sailed up in a large pontoon boat, a seven-meter, serial make, aluminum chassis, upholstered floor, seats in white faux leather, two outboard motors, 115HP Johnsons.

We asked him if he owned the boat. “I work here, I can drive what I want. I could take your boat if I wanted to.”

He brought along an icebox full of beer and a wireless speaker that kept blasting out country music.

“Let’s go,” he said.

As we boarded, he was already slightly drunk and as he drove, he became euphoric. He kept opening the beer cans with his teeth and foam dribbled from the corners of his mouth. It was clear he knew the bay inside out. He had sailed the Mississippi before, alone. Took him 12 days and nights, non-stop, on beer and amphetamines.

The locals here fish by speeding over shallow waters. The Asian carps are startled by the noise and jump up onto the deck on their own. These are big fish, up to five kilos. As he began to drive, they kept jumping out of the water. In the moonlight they shimmered like pearls.

“Shiiit! Hahaha! Welcome to America, motherfuckers!" he screamed and danced around the boat to the sound of country music. Two steps forward, two steps back, heels, toes. He took off his shirt and put his hat on backward.

“See! Like this. Just like surfing!” He spread his feet and pretended to surf. “You stand like this and jump”. He wanted to show us how to keep yourself on the deck at high speeds. “Jump! Yes! And again, jump! Come on, Anna Alabama, rev it up! Like that! Jump!”

Anna Alabama drove and he kept stroking her naked knee. He opened another beer can with his teeth. “You wanna fuck?” he asked me. Anna Alabama kept staring at the deck.

“ROOOAAAR”, the boat shook. “Motherfucker!!! Anna, stop!”

From who knows where he pulled out a knife, stuck it between his teeth and ran to the outboard motor. His head disappeared beneath the surface. “Hold my legs! I said hold my legs, motherfucker!” His head went below again. A fishing net had tangled around the propeller. “You got a light? Shine it here!” The knife shimmered under the light beam.

“Shiiit!!!” He spat out some river water and reached for another beer. “Gimme one! Everything’s fine. I got it all out!” Strings of frayed webbing flew through the air.

“Push it, Anna Alabama! Yeah! Oh, fuck! Did you see it? Close call, man!” An enormous carp jumped over the boat and missed his head by mere centimeters.

“Look at this!” His knuckled were swollen, bruised and scratched.

“What did you do?”

“He got into a fight yesterday”, said Anna Alabama.

“Who with?”

“You see that white speedboat?”

“Yeah.”

He shook his fist at the speedboat. “That nigger pulled up at the peer yesterday, pumped his gas and ran off. I fucked him up!”

“I hate them!”

“Who do you hate?”

“All these niggers, hate ‘em!”

“Why?”

“’Cause of history. They’re cunts! The mayor is a nigger bitch and she said to kill all the white kids!”

“She said what?”

“Yeah, that’s what she said. I know. All these fuckers want us dead.”

“Don’t hold it against him, he hates ‘em”, said Anna Alabama, “he grew up around here.”

“What about you?”

“I don’t care, they can be OK.”

“Come on, Anna, let’s dance.” He lowered the speed, let go of the wheel and took Anna to the bow. They danced. The boat drifted through the night, as he spun her around to a George Jones song.

Under the bridge he turned toward the mouth of the bay. Behind the peninsula, the Mississippi lazily dragged on.

“Look up,” he pointed to the bridge, “a guy jumped off from there last night. I dragged him out of the water. He was all blue, choking, spitting up blood. Broken ribs, broken arms and legs.”

“What happened? Was he drunk or on drugs?”

“No, he was Muslim.”

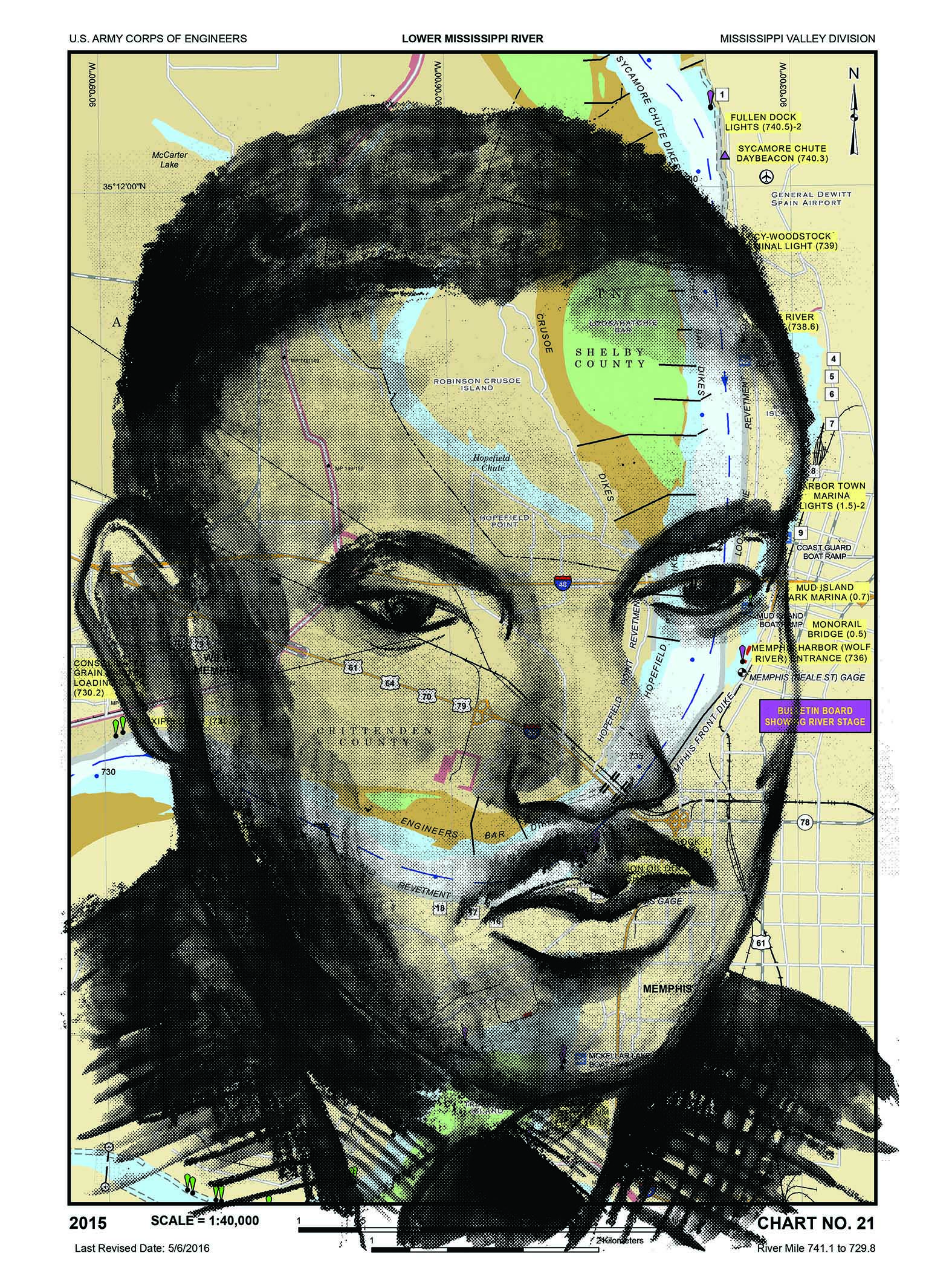

Memphis, April 4, 1968

6:01 p.m.

A deep inhale.

The right eye is closed. It twitches. The left is open wide, focused.

Tiny beads of sweat on the forehead. Nerves, not the heat, it’s evening, the beginning of April.

On the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine motel, a door has opened. A male silhouette entered through it. The man straightened his tie, gripped the balcony railing and looked down. Two white Lincolns stood at the ready to take him to the next meeting. The Lorraine motel neon sign shimmered in the dusk of evening.

He had still heard a quiet sound from across the street. A sharp pain followed.

The bullet pierced his neck.

Martin Luther King was pronounced dead about an hour later. He was 39 years old.

Memphis, October 1, 2019

9:21 p.m.

The white speedboat the kid told us about pulled up to the peer. A large black man in a white suit stepped off the boat.

“Whaaa-? I can’t believe it. What is that thing?

No, really? Crazy shit.

Haven’t seen one before.

It’s yours?

You sailed up in this?

Hahahaah!

From Minneapolis?

You guys are crazy.

Jack, Jack. Get out here. You have to see this!

And bring the ladies too.”

Everyone from the speedboat gathered around us. The steamer was a magnet. The speedboat’s owner’s name was Scooter. He wanted to see the boiler. He’d never seen a machine like that. They were on their way to set up his famous grill in the marina. Mississippi catfish, the secret Scooter recipe.

“Have you tried the catfish around here?”

All around us were “NO FISHING” signs that said the local fish cause cancer.

“Not yet.”

“Whaaaat? OK, you’re coming with us. Scooter is about to grill up the best catfish of your lives. I promise!”

Scooter lives off of his grill. He converted a bus into a restaurant and sells his own spice mixture for meats. He makes enough to be able to cruise with his friends around the bay on his white speedboat in the evenings.

“What happened with the kid from the marina?” we asked him.

“Eh, noting, ‘s all cool.”

“All cool?”

“Yeah. Kid’s got some problems but is OK, really.”

“Do you have problems because of racism here?”

“Meh. Used to be a problem. You’ve heard about MLK, right?” He thumped his fist to his chest. “Fuck the whites. They’re not the problem anymore. The biggest problem in the States these days – are the Mexicans.”

XII

We were leaving Memphis even more confused than when we arrived. The successive meetings with the “kid” then “Scooter” had not helped us to form an opinion on how things were standing.

We made a break during our stay with a night in Clarksdale to visit the Blues Museum, attend concerts and take the pulse of the city. We’d already been there several times during the preparation of our project. This is the town where Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil at the famous Devil’s Crossroads, and it’s also the only place where we had good espresso. For us it was the quintessence of the spirit of the blues, but in reality, we entered another poor city where life is punctuated by the influx of tourists during a music festival. At each of our stays we went to a sort of restaurant that had clandestine written all over it. There you’d get pieces of grilled meat and beer.

Every time we visited, this place seemed even stranger. To get in you push the front door directly from the street and enter a living room, with brown carpet on the floor and on the walls, garden furniture alongside a sofa from another time. There a grandmother has eyes fixed on the TV screen placed in front of her. Her husband, seated in a nearby chair, sips a beer staring into space, occasionally replacing his cap. This scene leaves you with the feeling of entering someone’s home without being seen.

A young woman comes to us, partly bleached hair, nails with experimental manicure, neon leggings exaggerating her few extra pounds, t-shirt size XXL, what would you like to drink?

We sit on the garden furniture, next to a table where men are playing poker. Two beers arrive, followed by red beans, mashed potatoes and grilled chicken.

In this 30m2 room there is the grandmother sitting on her sofa, her husband, the table of poker players, the young woman who serves and her younger brother. All are white.

The dishes arrive through a serving hatch cut into a door at the back of this room. I ask if I can use the bathroom, and the young woman tells me that I must go through this door, the serving door. There I come across a kitchen as large as the living room, one man is at the stove while another is preparing ribs in a sink, there’re also two others and they’re talking. All are black.

Like a mirror with two reflections, one white, the other black, separated by a bathroom and serving hatch.

I step into the kitchen, there’s a cutting board, sinks, a freezer, a fridge, an ironing board. I start a discussion with the man who prepares the ribs, I ask him what his recipe is, try to exchange banalities and then ask him the questions that are on the tip of my tongue. Yet despite the warmth of this young man, our conversation remained sterile. Impossible to get to know more, I was on the wrong side of the serving hatch, and they let me feel it.

We then went to Red’s, a hotspot for the blues in Clarksdale, and there too the same unchanging divisions: blacks play music and serve beers, whites dance and drink. No exceptions, none.